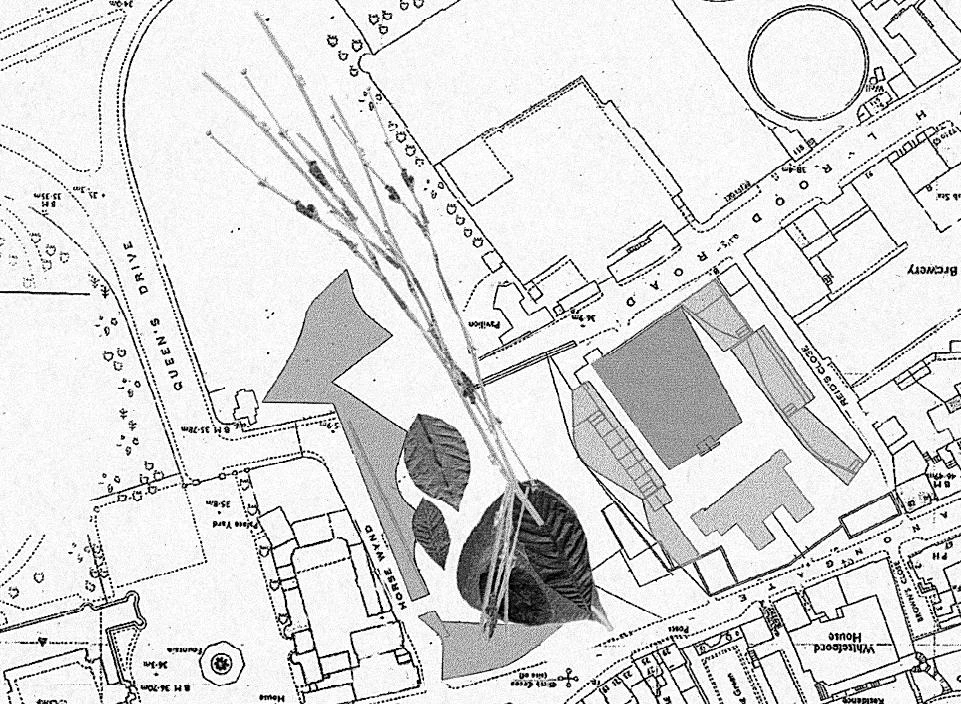

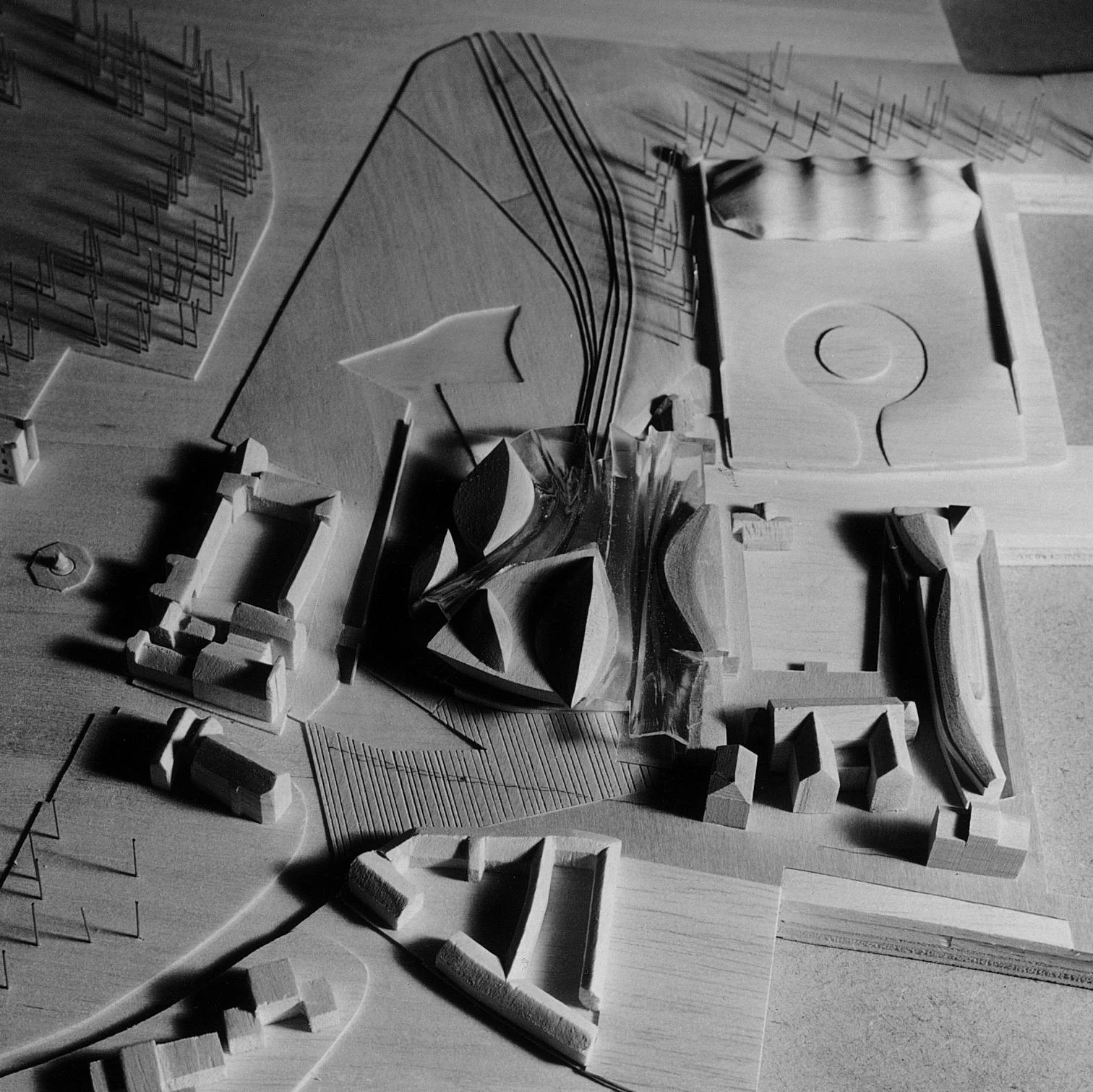

The competition drawings show a romantic, topographical project, with nautical and botanical resonances which builds a powerful symbol of the new Scotland in the delicate fabric of Edinburgh.

Unexpected, but not inexplicable: the election of the Catalan Enric Miralles as the architect for Scotland’s parliament building was a surprise; on second thought, however, it has a clear internal logic. In the absence of prominent Scottish architects, and given the insurmountable distrust that an Englishman would arouse, preferences almost inevitably pointed to a foreigner; and, what would beat a Catalan in interpreting the sentiment of a nation that recovers its right to self-government after three centuries? Moreover, Miralles’s age makes him an ideal candidate: at 43 he has sufficient experience to tackle a project of this physical and symbolical magnitude, besides being in a position to put the best of his energy into what could well be the work of his life. And, last but not least, his proposal was by far the best of the five finalists. Against the predictable routine of the American Richard Meier, the conventional modernity of the New York-based Argentine Rafael Viñoly, the schematic vulgarity of the Australian firm of Denton Corker Marshall and the strained disconcertment of the British Michael Wilford, Enric Miralles presented a lyrically expressionist project that matched up to the commission and the place.

The challenge of designing a parliament for a country with the personality of Scotland, and building it in the emblematic center of one of Europe’s most beautiful and conservative cities, has no precedent in the history of Spanish architects outside Spain. Neither Candela’s churches nor Bofill’s urban schemes and neither Calatrava’s stations nor Moneo’s museums have the mythical dimension of this seat of Scottish sovereignty. And Miralles has risen to the colossal stature of this challenge with a topographical and romantic project that amalgamates nautical and botanical metaphors, reconciling urban sensibility with expressive force, and that delicately blends into the historic fabric while creating a powerful symbol for the new Scotland.

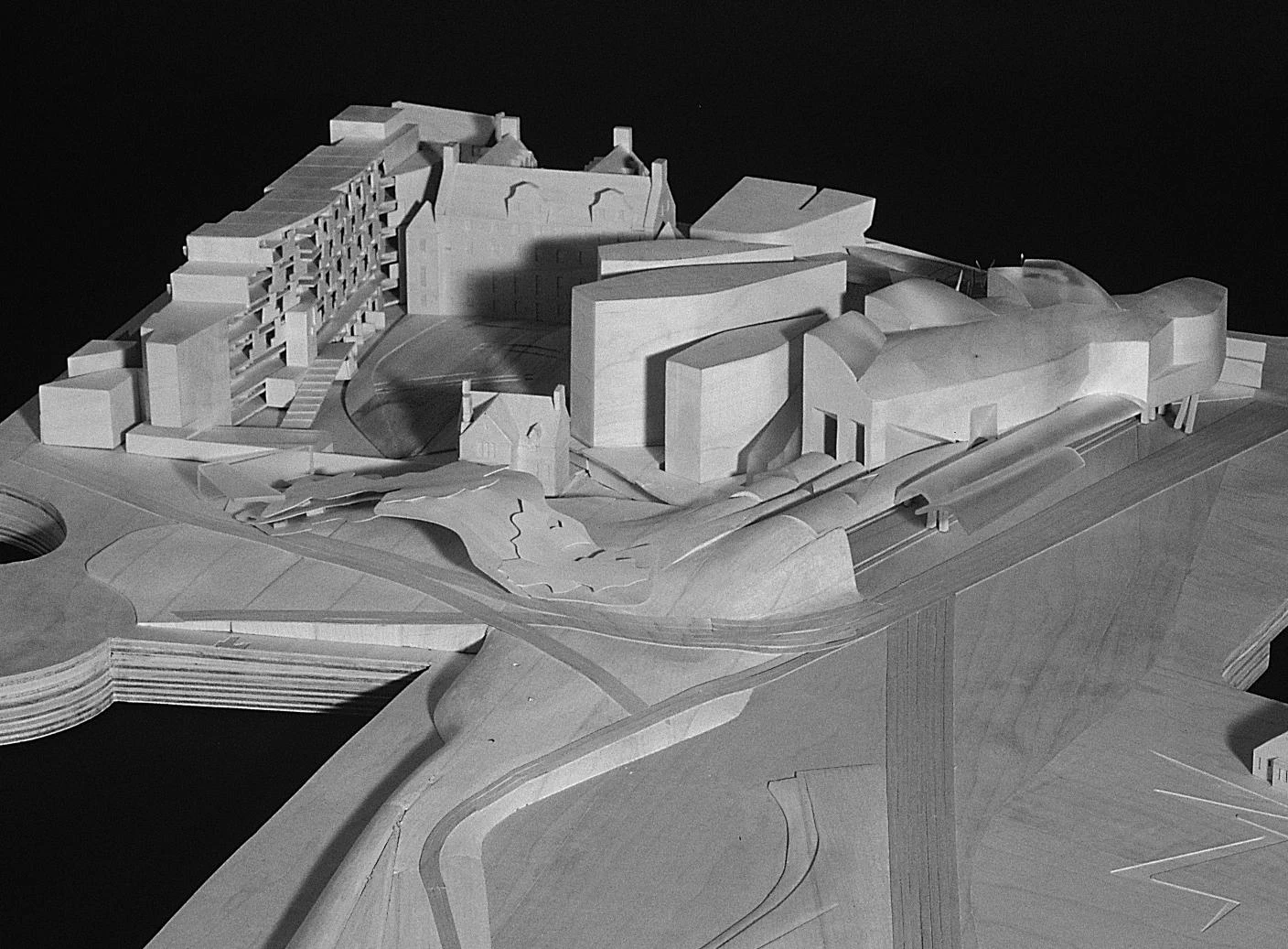

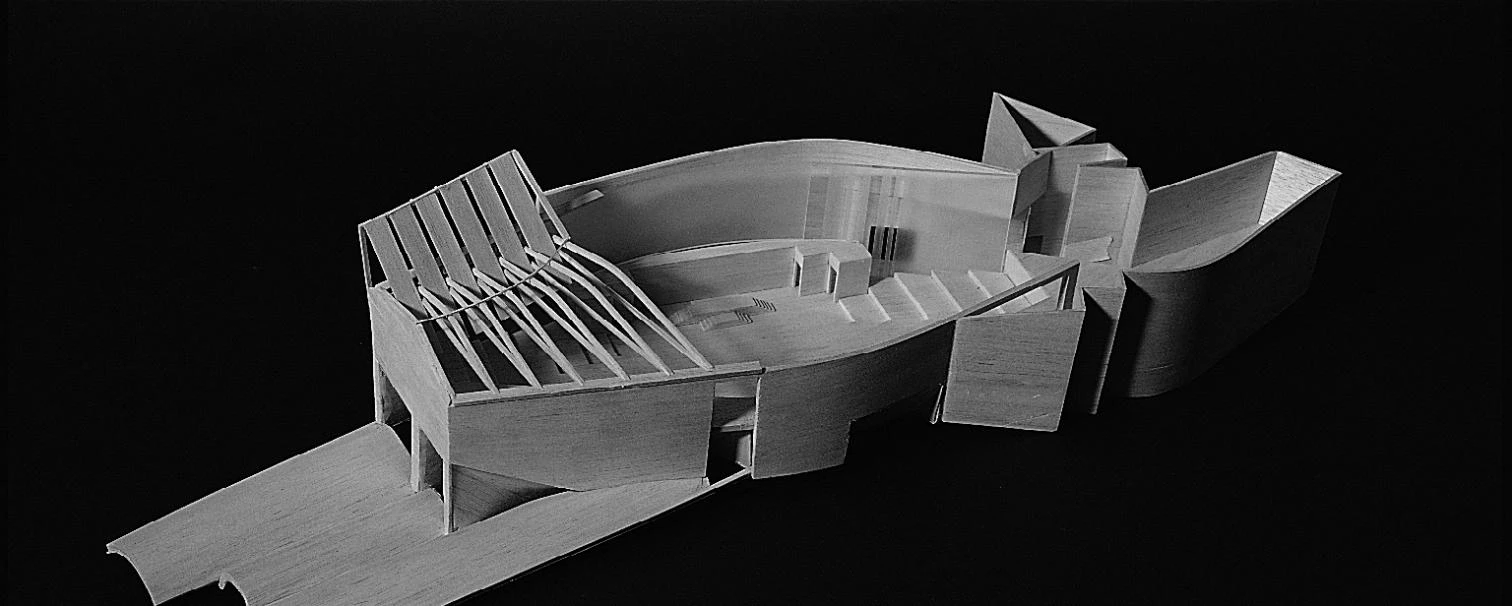

Close to Holyrood Palace, at the foot of the formidable rocky mass of Arthur’s Seat, and rounding off Canongate, the final stretch of Royal Mile, the Catalan architect has arranged the auxiliary facilities of Parliament around a cloister that brings together new and preexisting buildings, and crowned the large hall of the house of representatives as well as the smaller chambers with roofs that resemble inverted boats. All this at the far end of a terraced landscape that connects Parliament to the mountain, forming a huge natural and popular theater, and that stretches on to Canongate through two glass and wood passes between the tense arches of the stone walls, which rise like bows in a choppy sea. In an ideogram Miralles represents the session halls and the terraces as a cluster of fine leaves and a bunch of delicate stems, but the capsized boats, which relate to the vernacular dwellings that shipyard carpenters build with ribs and boards, are even more evocative, and it is this image that is likely to crystallize in the collective imagination.

Here Enric Miralles has avoided both the literal transparency of recent European parliament buildings – all determined to redeem discredited political elites through the forthrightness of glass –and the temptation to evoke the medieval surroundings. He has also stayed clear of alluding to Scotland’s more trivial figurative paraphernalia, from the tartan of Highland clans to the kilt or the bagpipe. Instead, he has merged his floral, dancing language – expressed in calligrams à la Apollinaire and photomontages à la Hockney – into a romantic nationalistic interpretation of Scotland that refers to the historical novels of Walter Scott and the folk-lore-rooted poems of Robert Burns. The boats over-turned by an uncertain gale and floating like leaves over crests of glass, and under which the tribe gathers, have the mythic and hypnotic force of legends sung by bards. At once light and essential, their lanceolated random shapes simultaneously express the tempests of history and the tenacious power of survival of the Scottish people, who pull through floods and shipwrecks with constructive ingenuity and vegetal obstinacy: an identitary and archaic nationalism all the more highlighted by the shape of the session hall, where the gentle curve of the rows of seats suggests cooperation more than conflict.

Labour’s Armada

In the competition organized by the secretary for Scotland, Donald Dewar, 70 offices from all over the world – 40 of them Scottish – were invited. On the basis of a questionnaire, 12 teams were selected, and further consultations narrowed the list to five finalists, none of them Scottish – at most, some associated with practices in Edinburgh. This, along with the fact that the institution to be housed by the building does not yet exist (as per the referendum that approved the statute of autonomy, the first parliamentary elections are to be held next May), triggered some controversy, a polemic nurtured by the close race in the polls between Alex Salmond’s Scottish Nationalist Party and Dewar’s own Scottish Labour Party, each registering 40% in the polls and vying for the privilege of heading the future government of Scotland. But the proposal presented by Miralles – in collaboration with his wife, the Italian architect Benedetta Tagliabue, and the Scottish branch of the firm RMJM – won the unanimous support of the jury and has been well received by Scottish architects. This should help him culminate his complicated day’s run amid political conflicts and the hostility of a sector of the press, which has called him “Dewar’s Spanish Armada” and ventured that he could end up being “the Titanic of the Labour Party.” With a £50 million budget, construction is to begin in the summer of 1999 and end in 2001, a race against time which will hopefully give the Catalan’s sails the wind he needs to leave the media storms behind and capsize his boats in Holyrood without the interference of shipwrecks.

The latest version of the project replaces the cloister and the upturned boats of the original proposal for a cliff of offices and the lanceolate petals of the meeting rooms, on both sides of the existing building.

In the city of the abrasive John Knox, many would have expected an architecture of Calvinist severity, one in tune with the demanding order of an enlightened Edinburgh and with the seamless continuity of its Attic and rigorist respectability. But the sure and elegant hand of Miralles has provided old Caledonia with a musical and romantic shaken symbol that belongs, as a parliament should, more to the nation than to the city, and whose friendly surreal volumes paradoxically express an identity through cosmopolitan images. Some will dismiss the building as yet another spectacular and extravagant construction of the century’s end, as a Scottish Guggenheim promoted by the mediatic obsession of New Labour’s Cool Britannia. Nevertheless, Miralles’s project also raises tricky questions about the representation of national sentiment, the rela tionship between figuration and abstraction, or the compromise between historical continuity and emblematic singularity in a Europe that integrates and fragments at the same time. His answers will not receive unanimous popular applause, and the Catalan architect had better prepare to be hounded by a multitude of bravehearts with blue-painted faces. To deal with these emulators of William Wallace, the best he could do would be to confront Mel Gibson with the rhetorical weapons of a bona fide Scot, the great Sean Connery in the role of a nonchalant James Bond, and with a scotch in his hand, simply say: “My name is Miralles. Enric Miralles.”