Change of Climate

The social and political climate of a planet divided by economic inequality starts to change in a year marked by Jihadist-inspired attacks and mass migrations.

The hottest year in history has also marked a turning point in the political and social climate of the planet. On the one hand, confronted with the colossal challenge that climate change poses for humanity, over two hundred countries have agreed to reduce their carbon dioxide emissions; on the other, a defensive sentiment has intensified among the privileged populations of America and Europe that seeks to raise walls against the world’s troubles, which this year have had their epicenter in a Middle East devastated by geopolitical strife and religious wars.

While the climate summit held in Paris put on the table the urgent need for global governance, nationalist populisms – stimulated by Jihadist barbarity, which struck twice in Paris, and by the impact of mass migrations – took the stage with figures like Donald Trump in the United States or Marine Le Pen in France, and these contradictory tides leave a bittersweet taste. For its part, a weakened global economy has slowed down the Chinese engine, with a stock exchange collapse that had a repercussion in other world markets; has shaken the political panorama of a Latin America much affected by the drop in the prices of commodities, debilitating the populist Bolivarian arch, from Argentina to Venezuela; and has created a difficult situation for a Europe that has proven incapable of organizing a unified stance in the face of the interminable crisis of Greece, the tragic threat of jihad, or the overwhelming exodus of Syrian refugees, and where Merkel’s sensible leadership has been tarnished by the scandal of the fraud in Germany’s most iconic enterprise, Volkswagen.

In Spain, the intense political year (Andalusian elections in March, municipal and regional in May, Catalonian in September, and general elections in December) resulted in a more fragmented political landscape with the appearance on the scene of new parties, Podemos and Ciudadanos, with reformist agendas formulated in reaction to the exhaustion of institutional systems undermined by corruption and growing economic inequality; and also in increased instability and uncertainty, intensified by the Catalan secessionist challenge to Spain’s Constitution.

Paris, host of the Climate Conference, suffered also terrorist attacks that rallied global support, in a year marked by the refugee crisis, inequality, and the surge of activist movements like that of the architects of Assemble.

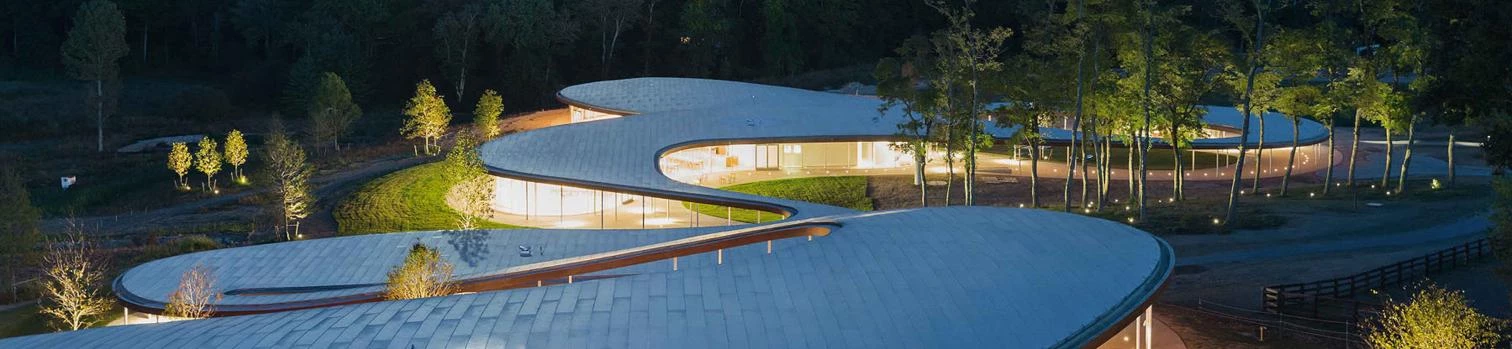

For architecture, the year of the discovery of water on Mars and the arrival of the space probe ‘New Horizons’ in Pluto – two NASA achievements that have brought humanity to its farthest frontiers – was marked on the one hand by bad news like the deliberate destruction of heritage by Daesh in Iraq and Syria, with the shocking blowing up of classical temples in Palmyra, and on the other hand by good news like the opening of important cultural works in the two superpowers, the United States (the Whitney Museum by Renzo Piano in New York, Grace Farms by SANAA in New Canaan, Connecticut, or the Broad Museum by Diller Scofidio + Renfro in Los Angeles) and China (the opera house by MAD in Harbin, the Long Museum by Atelier Deshaus in Shanghai, or the Folk Art Museum in Hangzhou by Kengo Kuma).

Grace Farms by SANAA, the Broad Museum by Diller Scofidio + Renfro (opposite page), the Fondazione Prada by Rem Koolhaas, and the new Whitney Museum by Renzo Piano are among the buildings of the year.

In the summer, attention was on the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the death of Le Corbusier, with a revision of his political trajectory during the Vichy regime, and on Expo Milano, where the prominence of pavilions like Britain’s by Buttress & Simmonds, Chile’s by Cristián Undurraga, or Austria’s by breathe-austria struck a constrast with the low profile chosen for Spain’s, a work of the firm b720, perhaps to be in tune with times of austerity. The same Italian city saw the inauguration, with controversy, of the Museo delle Culture by David Chipperfield – who was honored with a monographic exhibition at the ICO Museum in Madrid – and the opening, with acclaim, of the Fondazione Prada by Rem Koolhaas, who simultaneously though to less applause completed the Garage Museum in Moscow. Other objects of controversy were the inauguration of the Philharmonie de Paris, censured by its own author, Jean Nouvel; and the final commissioning of the Olympic Stadium of Tokyo to Kengo Kuma, with a project that vows to be cheaper than Zaha Hadid’s shelved competition-winning design.

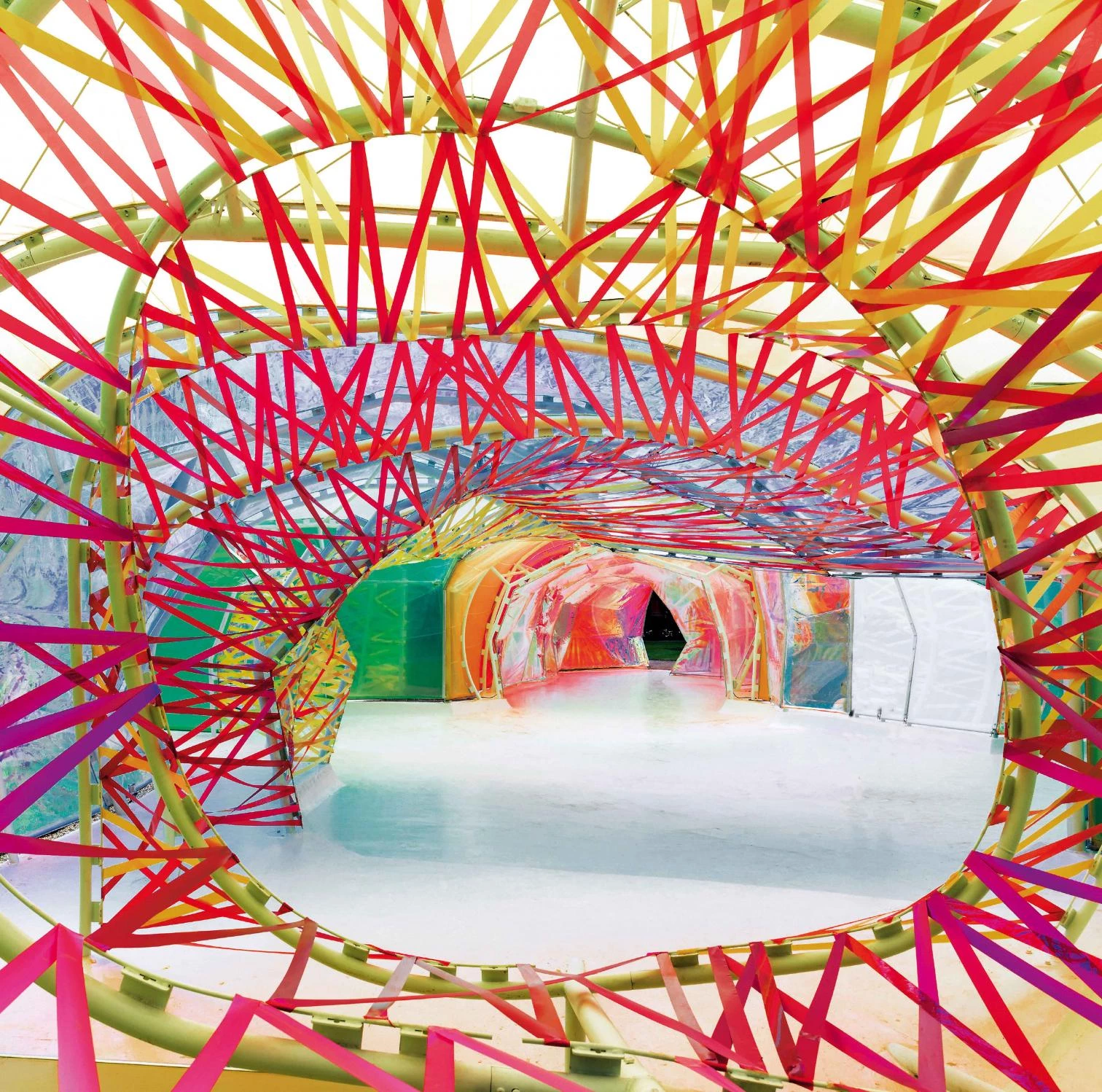

Two important pavilions were those of Jaque for MoMA PS1 and Selgas Cano for the Serpentine (this page), and two singular completions were the BBVA headquarters by H&deM and the Torun Auditorium by Menis.

Although the new climate of architecture is oriented towards the artisanal and towards activism (from the mythical Chinese artist and architect Ai Weiwei, who opened a show in London, his compatriots Wang Shu and Lu Wenyu, or the Vietnamese Vo TrongNghia to the Chilean Alejandro Aravena, appointed director of the next Venice Architecture Biennale, or the Brits of Assemble, recipients of an unexpectedly socially oriented Turner Prize), the big figures continued to deliver singular works: Norman Foster, who turned 80, inaugurated the imposing new City Hall of Buenos Aires for Mauricio Macri, who would later be elected president of Argentina, and a delicate winery for Château Margaux in Bordeax, while developing the visionary Drones project for Africa; or Herzog & de Meuron, who finished the building for the partnership’s own archives in Basel as well as a new stadium for Bordeaux at the same time that BBVA staff were moving into the colossal headquarters of the bank in Madrid, a new landmark for the capital nicknamed ‘The Sail.’

Madrid saw two major works finished, the innovative Giner de los Ríos Foundation by Amid.cero9 and the huge Royal Collections Museum, designed in 2002 by Mansilla & Tuñón and due to open to the public in 2016, but most of Spanish architecture’s achievements last year were abroad: Fernando Menis inaugurated the long awaited Concert Hall of Torun in Poland; Selgas Cano, Andrés Jaque, and Izaskun Chinchilla built much acclaimed pavilions in London (Serpentine Gallery) and New York (Cosmo for MoMA’s PS1 and Organic Growth for City of Dreams); González Hinz Zabala won the competition for the Bauhaus Museum in Dessau, and Entresitio, with MGP, for the National Museum of Memory in Bogotá; Barozzi Veiga received the European Mies van der Rohe Award for the Philharmonic Hall of Szczecin in Poland; Burgos Garrido, Porras La Casta, and Rubio Álvarez-Sala – with the West 8 of Adriaan Geuze – Harvard’s Veronica Rudge Green Prize for the urban project Madrid Río; and Nieto Sobejano were awarded the Alvar Aalto Medal in Helsinki, for their entire career.

Inevitably prominent in the chapter on awards are the Pritzker, bestowed on the German Frei Otto shortly before he died; the Praemium Imperiale, which distinguished the French Dominique Perrault; the RIBA Gold Medal, which went to the Irish partnership O’Donnell &Tuomey; the AIA Gold Medal, given to the Israeli-Canadian veteran Moshe Safdie; and the medal of the Spanish Association of Architecture Institutes, which was shared by two architecture schools, Madrid’s and Barcelona’s, and two foundations, Arquia and Arquitectura y Sociedad.

And the year that AV celebrated its 30th anniversary, it marked the centenaries of Josep Maria Sostres, João Batista Vilanova Artigas, or the photographers Ezra Stoller and Juan Pando, and mourned the death of the American Michael Graves, the British James Gowan, the Indian Charles Correa, the French Françoise-Hélène Jourda, the Mexican Carlos Mijares, the Argentinian Rafael Iglesia, the Portuguese-Mozambican Pancho Guedes, or Spain’s own Mario Muelas, Antonio Jiménez Torrecillas, and José Miguel Iribas, sociologist of tourism and missed collaborator of this magazine.